Original Post

March 8 is International Women’s Day (#IWD2016)—a global day celebrating the significant achievements of women and a reminder that urgent action is still needed to accelerate gender parity.

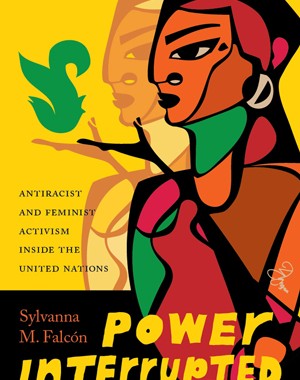

This International Women’s Day, we are taking the opportunity to highlight a new book on transnational feminist and antiracist activism from our Decolonizing Feminisms series. In Power Interrupted: Antiracist and Feminist Activism inside the United Nations, Sylvanna M. Falcón redirects the conversation about UN-based feminist activism to consider gender and race together. As the primary international institution that engages the issue of human rights, the United Nations has sponsored three World Conferences Against Racism (WCARs) and has been immersed in the debate around issues of racism for the past 50 years. The most recent, the 2001 World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance in Durban, South Africa, presented race and gender intersectionally in certain contexts, thanks largely to the concurrent NGO Forum Against Racism, which gave activists, advocates, and concerned citizens a space in which thousands could intensely debate and discuss the ongoing global challenges of racial discrimination.

The goal of antiracist feminists, particularly feminists of color from the United States and Canada and feminists from Mexico and Peru, was to expand the discussion of racism at the UN level, especially because the UN had not explicitly addressed the issue of racism on a global level since the 1983 WCAR.

Using a combination of interviews, participant observation, and extensive archival data, Falcón situates contemporary antiracist feminist organizing from the Americas alongside a critical historical reading of the UN and its agenda against racism. Her analysis of UN antiracism spaces, in particular the 2001 WCAR, considers how an intersectionality approach broadened opportunities for feminist organizing at the global level. The Durban conference gave feminist activists a pivotal opportunity to expand the debate about the ongoing challenges of global racism, which had largely privileged men’s experiences with racial injustice. When including the activist engagements and experiential knowledge of these antiracist feminist communities, the political significance of human rights becomes evident.

We spoke with Falcón about her book, publishing this spring.

Q: What inspired you to get into your field?

Sylvanna M. Falcón: Right after college graduation, I had the opportunity to attend the 1995 UN World Conference on Women in Beijing, China. Meeting feminist activists from all over the world was an inspirational and life-changing experience. I then moved to San Francisco and became associated with a youth-based human rights group and started to work at the Family Violence Prevention Fund (now called Futures Without Violence). Taken together—the Beijing conference and my time in San Francisco—I learned in an applied way about human rights as an organizing framework and method, about the challenges and promise of community organizing, and about the importance of public policy. Sociology as a field gave me both the flexibility and the structure I needed to investigate the questions I wanted to ask as part of graduate study. I also have a doctoral emphasis in Feminist Studies and this interdisciplinary field provided me with the methods, models, and tools to think about scholar-activism.

Q: Why did you want to write Power Interrupted?

SMF: I’ve been so inspired by all the women I’ve met doing human rights work in this region and I felt like their stories had been under-told. Of course other scholars have written about feminist human rights work at the United Nations, but I really wanted to tell the story of transnational feminist activism stemming from the Americas that had an explicit commitment to an antiracist politics. How do activists think about the confluence of patriarchy and racism and then apply this conceptualization of intersectionality in a radical way to ensure an inclusive visibility? How does a feminist approach to antiracism raise suspicion and distrust in other (non-feminist) activists who feel this nuanced approach derails the conversation about racial justice?

Q: What was the biggest challenge involved with bringing this book to life?

SMF: Writing a critical historical analysis of a mega institution to provide the context for contemporary activism was very challenging because I did not want to unintentionally give the institution credit for the activism that emerged in this space. The activism is the most important part of this narrative, yet its emergence did not come forth in a linear manner nor separate from an institutional structure. I refer to this challenge as the “circuitous milieu.”

Q: What was the most interesting thing you learned from putting together Power Interrupted?

SMF: At the first UN conference in 1945, the women representatives from Brazil and the Dominican Republic (Bertha Lutz and Minerva Bernardino, respectively) wholeheartedly embraced a feminist agenda while the US representative (Virginia Gildersleeve) publicly distanced herself from the women’s movement. In fact, a 1945 Washington Post article referred to Gildersleeve, in a positive way, as “no feminist thinker.” This discovery was an important reminder about the value of feminist genealogies to contextualize contemporary realities.

Q: What do you think is the book’s most important contribution?

SMF: A key contribution I make in this book is my assertion that the transnational feminist activism I discuss could only be possible in antiracist spaces. Thus, intersectionality gains traction at the UN as part of its agenda against racism by the mid-1990s following the downfall of South African apartheid and the independence of Namibia.

Q: How did you come up with the title?

SMF: I think the UN is a representation of power that is masculinized, racialized, hierarchical, and domineering and is often viewed institutionally as reflecting a US agenda. What antiracist feminist activists have done here is interrupt this power in such a manner that they also challenged a US agenda at the UN.

Q: What is your next project?

SMF: My next project is focused on transitional justice in Peru and about the challenges of building a human rights culture there. I am Peruvian American and like many children of immigrant parents, I often wonder what my life would have been like if my parents never left Peru. Thanks to my provocative conversations with human rights activists and artists in Peru, I have started to think about how social conflicts become obscured through an assertion of being “post-conflict” and about the importance of collective healing from trauma, which mandates challenging an entrenched culture of indifference to people’s pain and experiences with injustice.

Q: What are you reading right now?

SMF: Outside of the reading I do for my job, I have mostly been reading memoirs. At the moment I’m reading Life in Motion: an Unlikely Ballerina by Misty Copeland and prior to that book I read Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love, and So Much More by Janet Mock. In terms of novels though, I cannot recommend And the Mountains Echoed by Khaled Hossein high enough. Everyone I tell to read this book thanks me in the end.

Q: What would you have been if not an academic?

SMF: I’m a very organized person so maybe a party planner or a professional photographer since I love photos.